I first saw one of Peter Hujar’s self-portraits after falling down a rabbit hole of David Wojnarowicz’s essays, immediately seized by that dauntless look on the Hujar’s face, by his self-regard and composure. Hujar’s relentless stare didn’t seem to match up with the chronicles of friends that painted Hujar as a keen gossip, a social gadfly, a lusty raconteur. Hujar seems like a stoic, cornfed American boy—not the downtown artist whose portraits of cruising culture would end up enduring half a century. I sought out more, his portraits of Fran Lebowitz, John Waters, Candy Darling, that felt like short stories unto themselves. They return us to their moment—New York City in its (exhaustingly referenced) prime, these artists exhibiting a fin de siècle attitude of visceral creativity. Hujar made his name from such portraits, but his show at Raven Row gives us a staggering sweep of later works from the 1980s onwards that map both Hujar’s psychology and the subcultures of 1980s NYC.

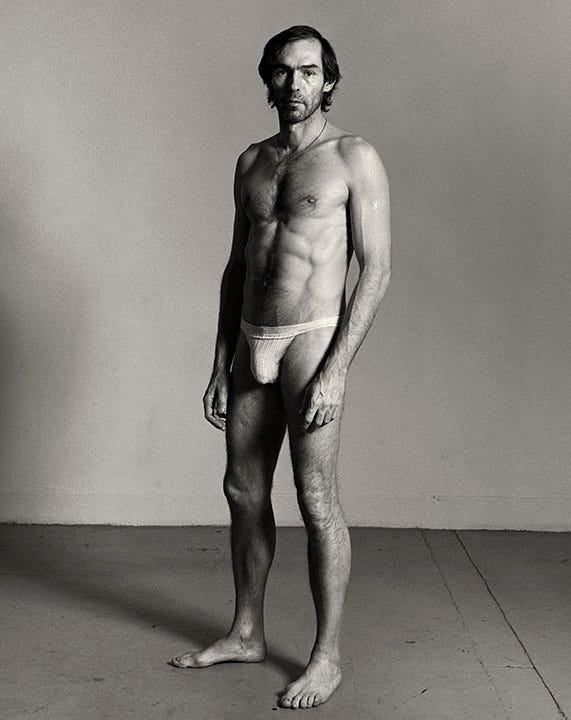

Hujar made a body of work from the bodies of his friends, lovers, collaborators, those who were all three at once. Many, like Hujar, died shockingly young, and many are mirrored in the work and personas of our intelligentsia today (think Hari Nef’s affection for Candy Darling or Jonathan Anderson’s reverence for David Wojnarowicz). Raven Row’s ground floor lays out his earlier works like some cast list for the rest of his life, in his life-filled, hope-filled prints.

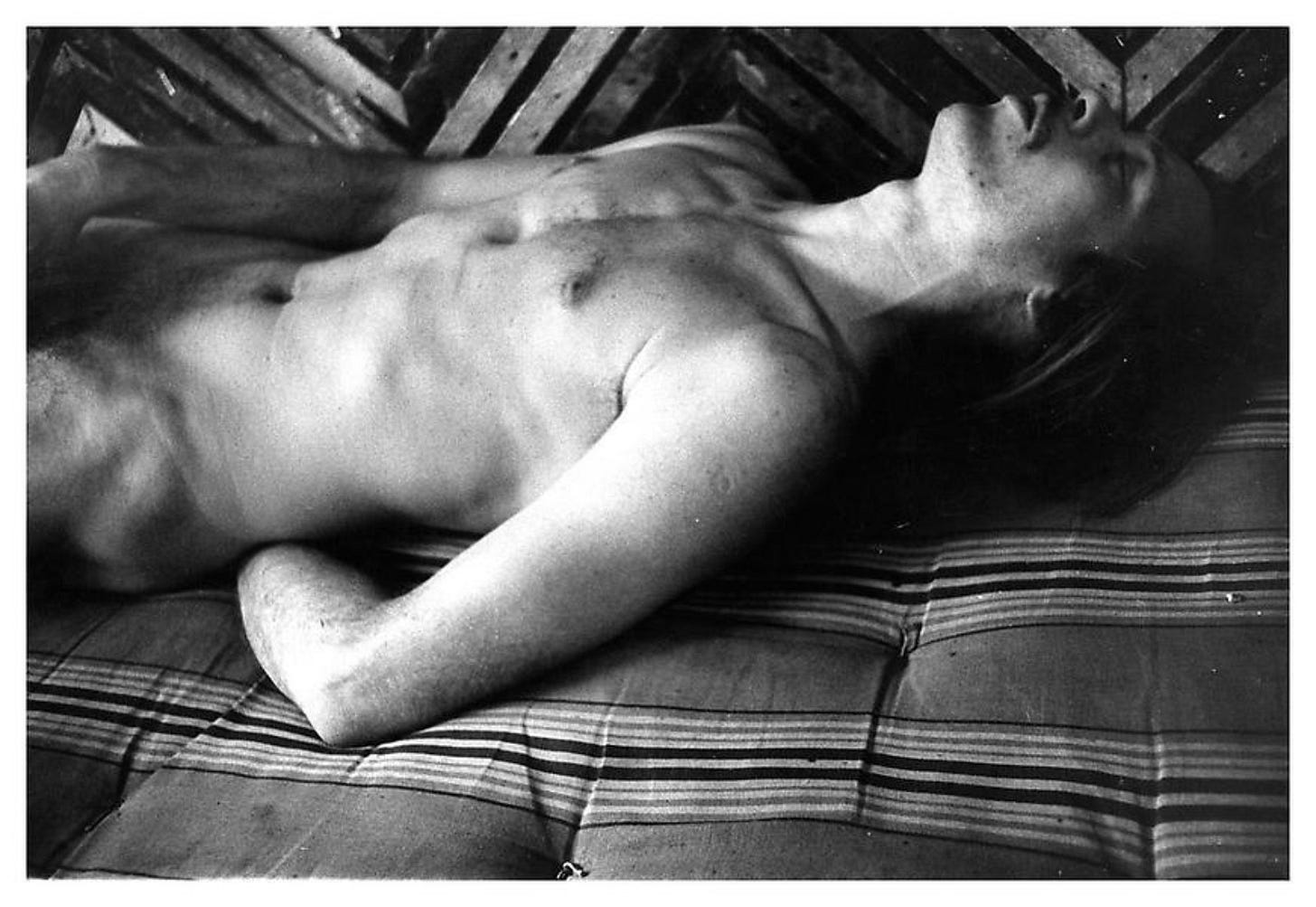

His style is empathy, and he glories in the moments of promise when a subject reveals themselves just enough for Hujar to seize on them. Hujar seems to capture the tension of these people at the exact border where they cross from who they are to who they want to be. It’s an incredibly fragile and gossamer thing, and it takes a kind of generosity to locate it. Hujar’s best friend Vince Aletti said that he “ held them under the camera eye until they let their defences down, and then he pounced”. That’s not to say he’s pinning these drag queens and rock stars to a wall, pressing their wings open like butterflies for display, but rather coaxing out the gesture that can reveal the person beneath the cabaret act. Hujar’s work always feels private, no matter how famous his subject. You feel like you’re being let in on something. Because of this, and because they became stars in their own right, his work became an idiom of its own.

It’s tempting in hindsight to view the cast of Hujar’s portraits as partygoers at the end of the world, either unaware of or distracted from the looming horror. But Hujar’s point of view is not about creating illusion or tethering us to the impossible visions of his brave new world—these photos ask us to bear witness. He made them look gritty, and good. It is hard. Hujar’s gaze cleaves apart the vision of the artist as they are, and the person that they want to be. In the expressions of Fran Lebowitz, Susan Sontag, or John Waters are exposed not only their efforts at sly seduction, but also their stories with Hujar himself, the way they trust and perceive him, and the way a shared fantasy can bring together two disparate artistic sensibilities.

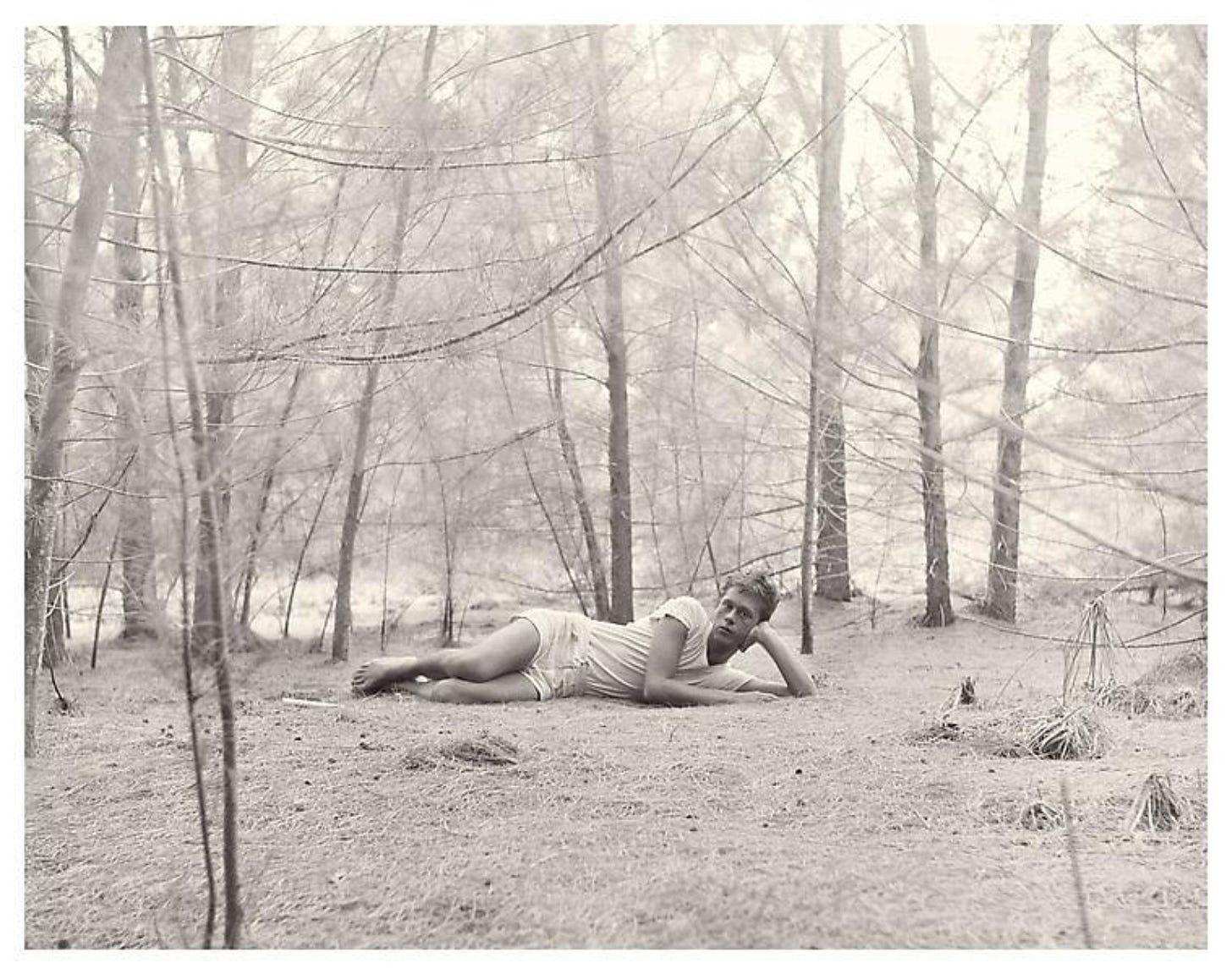

I’m reading David Wojnarowicz’s diaries at the moment, an artist more chimerical than Hujar, more sentimental as well. In his last diary entry, it’s Hujar whose spectre haunts the pages, with Wojnarowicz describing him as the “most important guy in my life”. Wojnarowicz is dying of AIDS, and the suffering is relentlessly and uniquely isolating, even more so than most pain. Wojnarowicz emerged on the scene some twenty years after Hujar, and their story unfolds across every floor of Raven Row—sometimes playful, sometimes threaded with longing, sometimes a melancholic mixture of the two. It shows Hujar’s most iconoclastic work, made by someone who deeply understands the chokehold of identity, the magic that happens in the moments when our constructed and natural identities collide. (“Your self…is other people, all the people you're tied to, and it's only a thread,” writes Tom Wolfe in The Bonfire of the Vanities).

Hujar’s roaming perspective of the downtown scene, its rusty cruising sites and its fertile green spaces, created an idiom of queer art that has been xeroxed many times over, as though Hujar were some messianic figure whose portraiture could render the spectre of the AIDS crisis something legible or even explicable.

In art as in sex, he was something of a maverick, and a terrifying period of depression from 1978 did nothing to diminish this. He had a reputation as a portrait artist by this point (though Hujar died with nothing close to the status he’s attained posthumously— “He was practically starving to death – and see how expensive his work is now”, Fran Lebowitz has said), and his classically composed shots of the New York rivers are shimmering visions of the city he loved. The overlapping currents of the lustful and the divine are brought out by this show, as the gallery suggests the opening up of Hujar’s perspective after his depressive period—like the world opening up from a pinprick to a wide lens.

Hujar’s vision of the era endures for their emotive power—Hujar being a glorious charmer whose portraits could only be the result of a natural conversationalist. We seem to have arrived at the point midway through the dialogue where the good stuff is happening. He stripped away the artifice of society, the contrivances of the downtown scene, invests them with his belief—that of the best born wits—that everyone has something to say, even if it’s about their loneliness, illness, or death.